Start Me Up Win95!

Thirty years ago today, Microsoft officially launched Windows 95 at its HQ in Redmond, Washington. By fate, I happened to be there as one of the engineers on the development team. This was the product that propelled Microsoft to the top, making it the world’s number one software company.

That year, I was assigned by Mr. Jamras Sawangsamud and Mr. Suthep Tannirat, executives of IRC—the company that developed the Thai language system on PCs—to work on Thai language support for Windows 95 together with the development team at Microsoft HQ. It turned out to be a year of immense learning, in both adaptation and heavy responsibilities. Even though some colleagues later flew in to help, I still had to take on the entire system work from start to finish.

Embedding the Thai language into an operating system like Windows 95 required changes at a much deeper level than just hooking into ordinary apps. Various system components had to understand the codes and language services in a consistent way. Protocols like COM, used for communication between applications, were brand-new at the time. Supporting languages beyond ASCII had to be done very carefully and aligned with official standards.

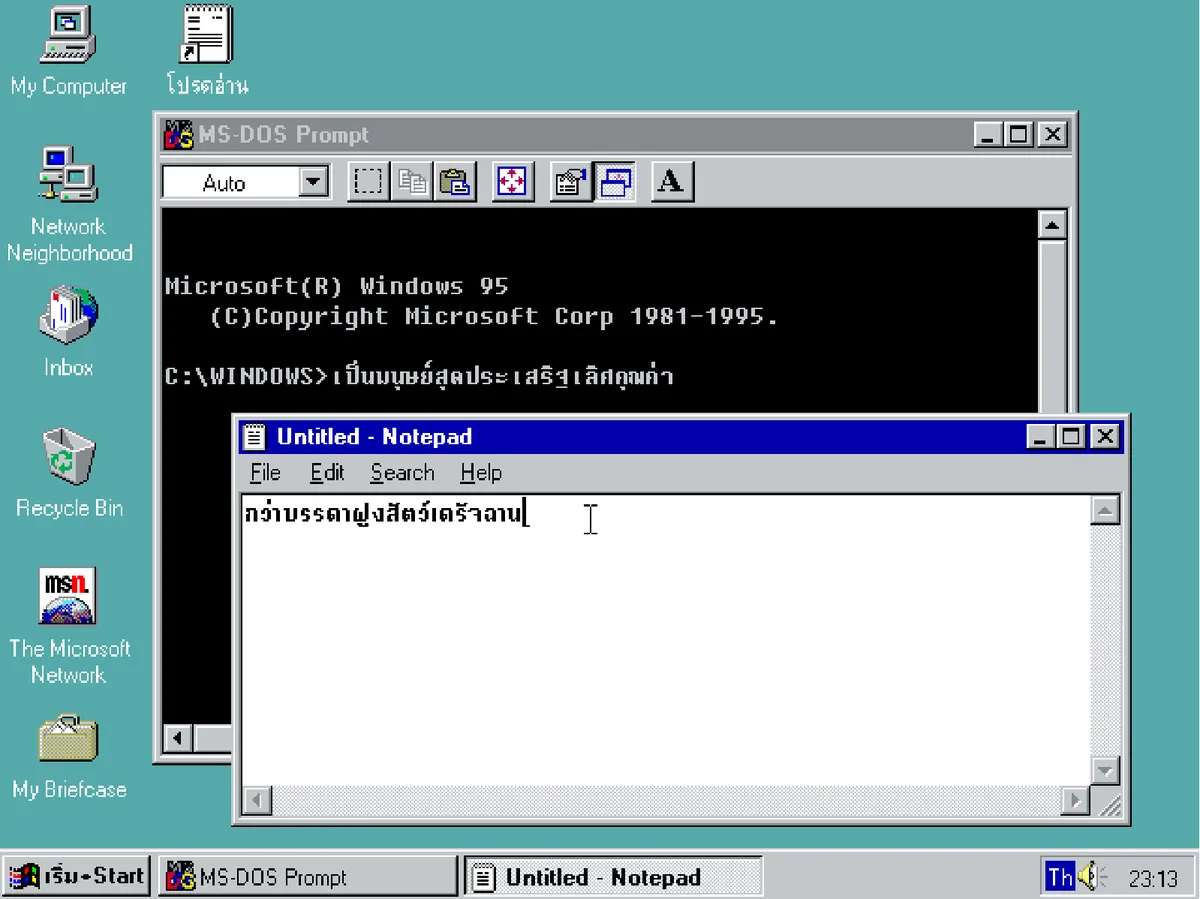

Inside Windows 95, two systems ran side by side: the old DOS and the new graphics system based on 32-bit architecture borrowed from Windows NT. Thai language support had to work across both DOS Thai apps and older 16-bit Thai Windows apps. Since Thai apps used the Thai SDK Extension—which Win95 didn’t support—I had to write a compatibility layer embedded into the loader. This intercepted the export table of the code being loaded and redirected it to the new system services. You could call this a hack. This was critical for the Thai market, since many Thai apps would not load otherwise.

As for DOS, it wasn’t actually DOS but rather a VM, or virtual machine. The DOS command services had their own memory and I/O management and communicated with the Windows VM through interrupts. For copy & paste, not only did data have to be moved, but code conversions were required too, since DOS used IBM-defined OEM 8-bit encoding, while Windows used ANSI. Keyboard states, mouse handling, sound, and printing were shared functions across all VMs.

Then there were the built-in applications. The most demanding were WordPad and Exchange, Microsoft’s new email program. Both apps were built on the RichEdit control, which was based on the new RTF format. RTF could be opened by all Office applications and was used to store emails with embedded images and sounds. RTF was the first document format to specify a charset per language, tied to keyboard and font usage. Thai used charset 874 together with font signature 222—standards that persisted in Word and email documents for many years until Unicode became the permanent standard.

Every part of the system had to handle Thai input and output seamlessly—display, printers, fonts, and language services like Thai dictionary sorting, word breaking, keyboard layouts, and even details like currency, Thai numerals, date formats, and the Buddhist calendar. A single bug in any of these areas could cause catastrophic failures, such as breaking databases using protocols like ODBC.

Windows 95 represented a major technological shift—not just in what users could see, but in how software communicated at the protocol level. It changed nearly every key data format, and it transitioned software development to 32-bit—all at once.

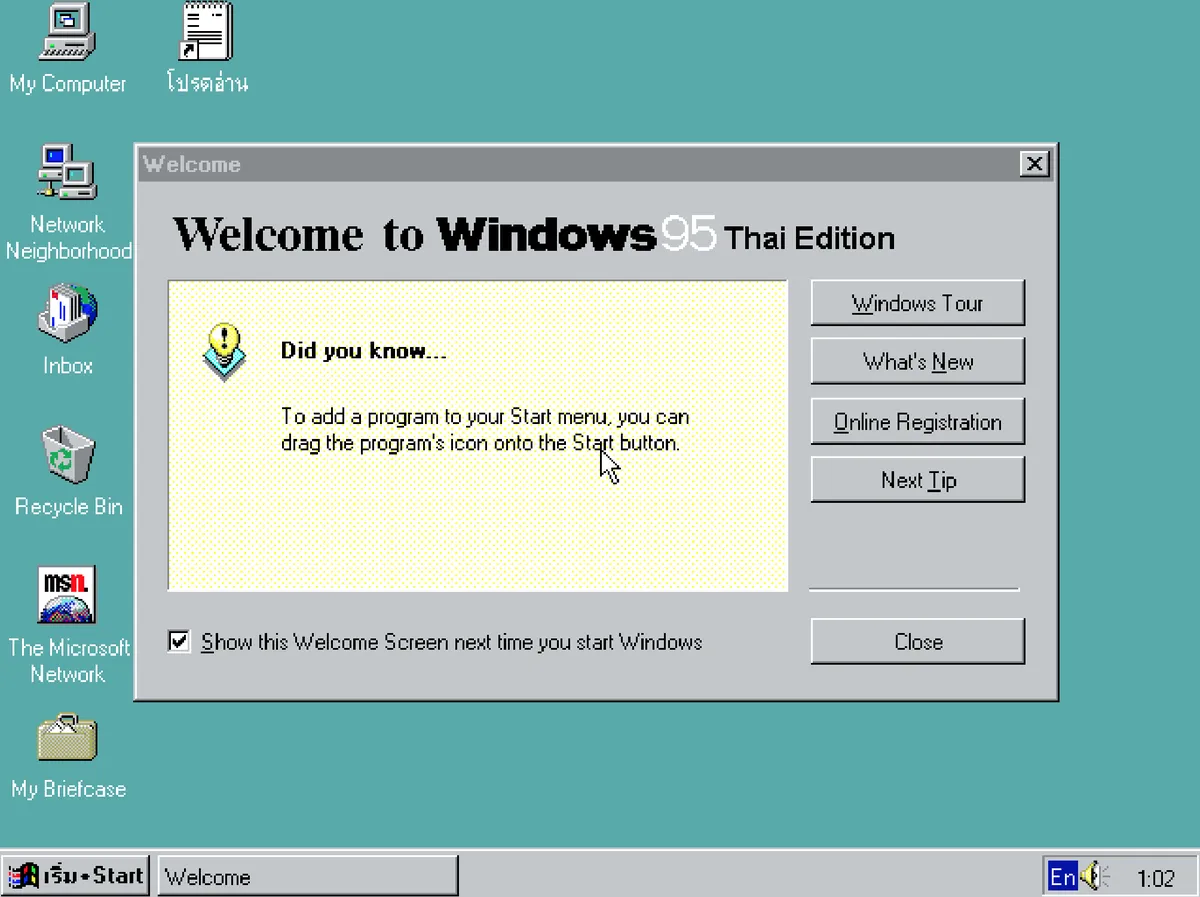

Another structural highlight of Windows 95 was the first attempt at multilingual support within a single codebase, called Langpack. Instead of splitting code into language-specific products, the idea was to unify it. Although it wasn’t fully successful at the time, it laid the foundation for the true multilingual system that was perfected in Windows 2000, when the NT and Win9x codebases were merged. Thai language support was a key stepping stone toward the multilingual systems we use today—on both PCs and mobile devices.

Because of the project’s complexity and my own inexperience, I had to stay in Redmond for nine months. I dissected every piece of code that passed my eyes and read every spec I could find. Each day passed without a sense of time, with no mentors or guides—everyone was busy with their own work. The morning I finished the master disk of Windows 95 with Thai support, I sat by myself by Lake Bill, a small pond on campus, watching a flock of ducklings play in the water until dawn, too exhausted to stand after working all night.

Not long after, the Thai edition was released to the market. It was the second language supported, after Japanese, and came out only three months after the English version. Microsoft had only been in Thailand for about a year, but with little preparation time, Windows 95 was launched, opening a new era in the Thai computer industry.

On the afternoon of Launch Day, August 24, 1995, I remember someone rushing me outside the building, handing out T-shirts of different colors to wear. I got an orange one. We crowded into the main auditorium before heading out to the stands set up behind a giant outdoor tent filled with reporters. Then the backdrop opened, and Brad Silverberg, the big boss on stage, introduced the development team—about two hundred of us—while the Rolling Stones’ Start Me Up blasted through the speakers. My orange T-shirt became part of the Windows Flag logo displayed behind us that afternoon.